Easter Supplement

The Resurrection is cornerstone of the Christian faith

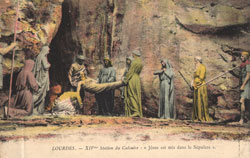

This historic French postcard depicts Jesus being carried into the tomb and is the 14th Station of the Cross at the Shrine of Our Lady of Lourdes in France. Christian faith in the Resurrection has met with incomprehension and opposition from the beginning. Yet it has always been, and remains today, the cornerstone of the Christian faith.

(Illustration/historic postcard)

By John F. Fink

This Easter, we Christians reflect on one of the basic doctrines of Christianity—the resurrection of Jesus from the dead.

It’s such a basic belief that St. Paul told the Christians of Corinth, Greece, “If Christ has not been raised, your faith is vain” (1 Cor 15:17).

But this is more than religious belief. We Catholics are convinced that the Resurrection is historical fact. Christianity is based on that historical fact.

It’s easy to understand how people without faith can doubt the Resurrection. It just isn’t within our modern sphere of experience. Well, it wasn’t within the Apostles’ sphere of experience either.

Our belief in the Resurrection is helped by the fact that the Apostles doubted it. They weren’t gullible men who easily accepted something like a man coming back from the dead.

As often as Jesus predicted that he would rise from the dead, the Gospels make it clear that the Apostles didn’t understand what he was talking about.

They didn’t even believe the women who went to the tomb and returned with the news that they had seen the risen Lord. Surely, they thought, the women were delirious. It took Jesus’ appearance to them, coming into a locked room and eating with them, before they believed.

People today who don’t believe that Jesus actually rose from the dead must think either that the first Christians were awfully naïve to believe such a thing or that they were extremely clever to be able to concoct such a story and then sell it, not only to their fellow Jews, but also to Gentiles all over the world.

Gospel accounts of the Apostles, though, show clearly that they were simple and uneducated men, hardly the type who could plan and successfully carry out a gigantic fraud.

The news about Jesus’ resurrection from the dead spread by word of mouth for decades before it was put down on paper. It was St. Paul who first did that, in that letter he wrote in the year 56 from Ephesus, in modern Turkey, to the community he started in Corinth.

This letter was written about 26 years after Jesus’ resurrection, and before any of the Gospels had been written. If there were earlier written accounts, they have not survived.

In that letter, Paul reminded his readers, “I handed on to you first of all what I myself received, that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures; that he was buried; that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures; that he appeared to Cephas [Peter], then to the Twelve. After that, he appeared to more than 500 brothers at once, most of whom are still living, though some have fallen asleep. After that he appeared to James, then to all the apostles. Last of all, as to one born abnormally, he appeared to me” (1 Cor 15:3-8).

In other words, many people saw Jesus after his resurrection and could attest to it.

Christians are generally familiar with most of the appearances that Paul enumerates, plus a few others written about in the Gospels of John and Luke—to Mary Magdalene, the two disciples on the road to Emmaus and the seven Apostles who were fishing in the Sea of Galilee.

John’s Gospel gives us details about his appearances to the Apostles, first when Thomas was absent and again, eight days later, when he was present.

We assume that Jesus’ appearance to 500 brothers is the same account that Matthew gives at the very end of his Gospel when he says that the 11 disciples made their way to Galilee, to the mountain to which Jesus had summoned them. Apparently about 500 people assembled there with the Apostles.

We are less familiar, though, with the appearance to James. This is not James, the brother of John. That James was among the Twelve when Jesus appeared to them. This James was the leader of the Church in Jerusalem when Paul was writing to the Corinthians. He was well known among the early Christians, which is apparently why Paul referred specifically to him.

Surprisingly, though, we are not sure of James’ precise relationship to Jesus. He might have been a cousin, but Paul referred to James as “the brother of the Lord” (Gal 1:19).

According to an early Christian document, the Protoevangelium of James, James was the eldest of four sons and two daughters of Joseph by an earlier marriage. Joseph was a widower, older than Mary, whom he married so she could help him raise his children. He considered himself Mary’s protector and was willing to honor her vow of virginity. The other three sons, named by both Mark and Matthew, were Joseph, Judas and Simon. (Simon succeeded James as bishop of Jerusalem after James was martyred in the year 62.)

St. Jerome, in the fifth century, wrote about Jesus’ appearance to James in his book De Viris Illustribus. He wrote that he had recently translated into Greek and Latin the early Christian document titled “The Gospel according to the Hebrews,” which still exists today but is not included in the New Testament.

It says that James “had made an oath to eat no bread after he had drunk the cup of the Lord until he saw him risen from those who sleep.” It then says that Jesus appeared to James, took some bread, spoke a blessing, and gave the bread to James with the words: “My brother, eat your bread, for the Son of Man is risen from those who are asleep.”

Up to that time, James had been skeptical of his younger half-brother. John’s Gospel stated, “Not even his brothers had much confidence in him” (Jn 7:5), and Mark’s Gospel reports that Jesus’ family at one point thought he was out of his mind (Mk 3:21) and went to take him home.

After Jesus’ appearance to James, though, James devoted himself to preaching the Gospel to his fellow countrymen, the Jews, and was the acknowledged leader of the Church in Jerusalem. He is mentioned prominently throughout the Acts of the Apostles.

Paul’s letter to the Corinthians was then, and is now, the basic teaching of Christianity about Christ’s resurrection. Paul was insistent about it when he wrote to the Corinthians, saying that our very salvation depends upon the fact that Jesus rose from the dead. Christians are not given a choice in deciding whether or not to believe in the Resurrection.

Some people confuse resurrection with resuscitation. Christians do not believe that Jesus was only resuscitated as he himself resuscitated Lazarus, the son of the widow of Nain and the daughter of Jairus.

Jesus rose from the dead with a glorified body, one that could pass through the locked doors where the Apostles stayed, one that could appear to the disciples on the road to Emmaus and could just as quickly disappear. And yet it was Jesus’ body, one that Thomas could touch when he was invited to examine Jesus’ wounds.

Christian faith in the Resurrection has met with incomprehension and opposition from the beginning.

In the early fifth century, St. Augustine wrote, “On no point does the Christian faith encounter more opposition than on the resurrection of the body.”

Yet it has always been, and remains today, the cornerstone of the Christian faith.

(John F. Fink is editor emeritus of The Criterion.) †